Complexity theory and building a network

25th March 2023

Trauma Informed Care expert Angela Kennedy who is TICA lead here at the AHSN NENC shares her thoughts on complexity theory and building a network this week on the blog.

When we work towards changing culture and practice, those of us in public service often use project management tools. These are very helpful in structuring workplans and keeping on task. We often use pathways to help the flow of people through a process. These can be helpful in smaller trauma informed change projects.

However pathways can sometimes not be as flexible as people need and project frameworks are more limited when human systems are the focus of the outcome. Programme management can be useful when juggling many projects towards a goal in a bigger system. A good logic map is great for making sure that enough ingredients are present and nothing superfluous to the outcome is detracting from efforts. However social change is more of a ‘movement’ than a business and as such can benefit from thinking about the nature of social growth.

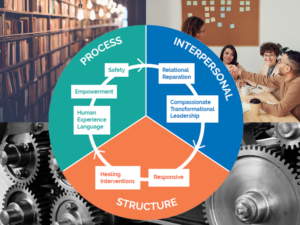

There is a framework guiding the leadership of the TICA community and can be useful in nudging the change in cultures that those involved want to see. Complex Systems thinking is potentially useful in human systems because of the interactions ‘are bigger than the sum of its parts’. The properties of complex systems are illustrated below in relation to the changing systems towards a trauma lens.

- Interactions. The parts relate to each other and their environment in numerous ways. That means they can’t easily be studied in isolation from each other. When we did a rollout of TI on a ward, the conversations and learning and motivation spread by osmosis to other areas that related to those wards. TICA attempts to utilise the 1000 members to spread good practice through the interactions they have with each other and the public services that they are part of.

- Emergence. The TI culture can’t be predicted by looking at components alone. What emerges from and between the components may look different to what was expected. This is why TI implementation needs some top down buy in, needs to allow bottom up innovation and autonomy, why language and operational policies matter, why the relational quality of human interactions makes a difference.

- Dynamics. In project management, change is assumed to be linear and based on doing some things in a certain order to achieve the desired future state. This may work for building a house but recovery from trauma and maintaining good staff wellbeing requires attuned and adaptive relationships that fit the person in their context at that time. Its variables can change in unpredictable ways over time and at different paces. TI needs to watch for unintended consequences, keep integrity via its fluidity and keep its relationships humble and mindful. Reaching the ‘tipping point’ to sustained TI ways of doing things is proving a challenge. Services often revert to the status quo. It is easier to set something up new than it is to change what is there but drawing on staff with behaviours from pre-existing services still endangers progress with a pull back to the old paradigm.

- Self-organisation. This principle is that there doesn’t need to be a primary leader or goal but that the culture and outcomes are created through small multiple efforts. The focus in TICA was to create a space for all those bottom up examples to shine. It has faith that the different narratives of TI will coalesce over time into an agreed new paradigm. Leadership of TICA has required me to be quiet even when I may have strong opinions and find ways to select and include lots of voices and projects with their views and hold the space for something new to emerge from distributed leading.

- Adaption. Through learning, through networking and through decisions to select some ways of doing things, our public services can change over time towards TI goals. TICA is space for that learning, it is a place for researchers to find participants and it has involved commissioners towards making some decisions.

- Multi level measurement. Ways of measuring what we do needs to reflect the complexity and nuances of our emerging TI states. This isn’t to negate the linear ways we have a measuring change but it is to ensure that we use many perspectives on change and that we do not assume that change is from bad to good but rather towards a different state. One example is the development of ROOTS, a tool to support TI growth that can be tailored to context and finds TI in the process of change as much as the end product.

The community used sensemaker as its method of choice to evaluate the futures platform because this method has its values in complexity theory.

Such a framework is gaining popularity I notice. Or rather, some of its language is being adopted, eg, the term ‘wicked problems’ is being applied in Integrated Care Systems to describe the entanglements between things that can be hard to grapple and influence, such as, the influence of poverty or community disadvantage and mental ill health. Wicked problems are often described as those social issues that are interconnected but lack clarity of a solution and can’t be solved in a risk free manner. Whilst the rates and influence of trauma and adversity may count as a wicked problem, I would argue that there are ways to tackle it, if the will and investment is present. The framework for change helps to draw out the steps that we can collectively do towards this aim.